D.O.Ca. Rioja

The oldest records of Castilian, the most common dialect of Spanish, come from a 13th Century monastery in Rioja, and speak of wine. This is not surprising, considering Rioja’s importance in the Spanish wine industry. Rioja has been growing grapes and producing wine since before the arrival of the Romans, but like other regions in Spain, the winegrowing industry burgeoned under Roman rule. Many Roman lagares, or pressing troughs, are still intact and in use today across the undulating hills of Rioja Alta and Alavesa. Under Moorish rule winegrowing was tolerated rather than banned, but once again, the wine industry flourished after the reconquest, when monks would care for vines and vinify grapes for use in Mass and for their own personal consumption.

Rioja came to prominence in modern times, strangely enough, because of Bordeaux. Due to the powdery mildew plague of the 1840’s in Bordeaux and the phylloxera plague in the late 1860’s, Bordelaise merchants and winemakers travelled to Rioja Alta in search of wine to fill the hole left by these plagues. This caused another surge in the industry, and many of Rioja Alta’s most famous families and bodegas entered the industry in order to supply the French – including Bodegas Muga. These pinnacle producers, who now enjoy prominence in international markets, were founded and supplied the French from Barrio de la Estación (neighborhood of the [train] station) in Haro. Riojan bodegas would load train cars with enormous barrels filled with wine, and ship them to Bordeaux.

The Bordelaise returned the favor to Rioja, by educating them on barrel ageing. For almost a century following, Riojan wines were synonymous with élevage in American oak, which was used instead of its French counterpart because it was far cheaper. This traditional of ageing in American oak continued through the end of the 20th Century when a few pioneering producers, including the Eguren family, started introducing French oak. Many of the staunchest traditionalists in Rioja still use exclusively American oak for their wines.

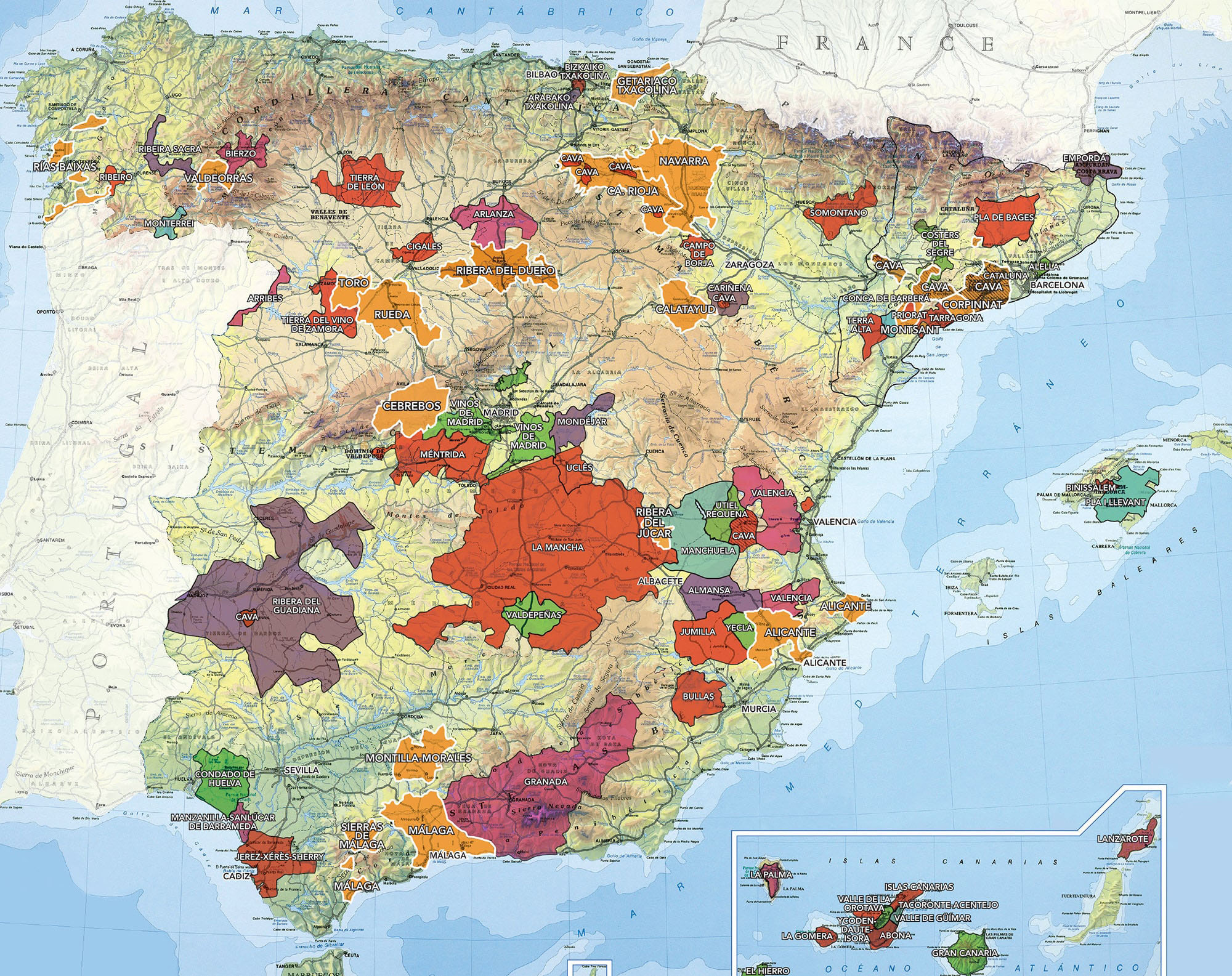

Rioja is one of the two Denominaciones de Origen Calificadas, which is the highest level of denomination that Spanish wine regions can achieve. D.O.Ca. Rioja is distinct from La Rioja, the province of the same name, as the D.O.Ca. spreads into parts of the provinces of Navarra and Álava, which is considered to be part of the Basque Country.

Rioja’s prestige and ability to produce outstanding wines filled with a sense of place stems from its unique, diverse geography, and variety of terroirs. It is impossible to describe the region in one blanket statement, as the three distinct subzones – Rioja Alta, Rioja Alavesa, and Rioja Baja, are each wildly different in a variety of senses. Differing cultures, traditions, soil types, mesoclimates, geographies, altitudes and more combine to differentiate the three.

Rioja Alta, the original commercial subzone that was connected with the French, is the location of several of Rioja’s most traditional bodegas, located around Barrio de la Estación in Haro. Bodegas Muga, long time partner of Jorge Ordóñez Selections, is perhaps the most prominent producer in Haro. San Vicente de la Sonsierra is one of the most desirable towns in the region, and is home to the Eguren family, who Jorge Ordóñez has represented since 1989. San Vicente de la Sonsierra is home to the Eguren’s Señorio de San Vicente, the bodega that produced Rioja’s first single vineyard wine. It is impossible to describe Rioja Alta’s terroir with a blanket statement, but the soils tend to be more clay dominant than neighboring Rioja Alavesa, also home to several of the Eguren family’s estates.

Rioja Alavesa, pinned between the northern bank of the Ebro River and the foothills of the Sierra Cantabria mountain range, could not exist as a viticultural zone if it were not for these mountains, which shelter the vineyards from the Atlantic weather systems. From the northern banks of the river to the foot of the mountain range, Rioja Alavesa ranges in elevation from 400m above sea level to 800m, indicative of the myriad varying vineyard sites in this zone. The soils in Rioja Alavesa are far more limestone dominant than in Rioja Alta. Tempranillo is still the main indigenous variety, and other later ripening Riojan varieties, such as Garnacha and Graciano, have trouble reaching full maturity when planted at higher altitudes near the mountains. Given the undulating terrain, varied soil types, and changing altitudes, Rioja Alavesa is home to an abundance of incredibly unique and high quality single vineyard wines – Viñedos Sierra Cantabria is a perfect example.

Long perceived as the lower quality brother to its two northern neighbors, Rioja Baja encompasses everything southeast of Logroño. A far warmer climate than Rioja Alta and Alavesa given its more southern location and proximity to the Mediterranean, Rioja Baja is far more diversified in its agriculture than its two counterparts. That being said, viticulture is still extremely important in Rioja Baja, and for many decades, has supplied Rioja Alta and Alavesa with valuable Graciano and Garnacha, as these varieties struggle to ripen in the northern regions. In recent times, Rioja Baja has started to be valued as a quality wine growing region. Rioja Baja’s soils are far more alluvial than Alta and Alavesa, and as mentioned, warmer climate varieties such as Graciano and Garnacha thrive here. Bodegas Ilurce, along with Jorge Ordóñez, pioneered the production of a high quality, affordable, single varietal Graciano wine. In the early 2000’s, 100% Graciano wines were either unaffordable, or low quality, and Rio Madre changed that trend.

Given Rioja’s popularity in the international marketplace, corporate wineries have entered the space and have abused Rioja’s ageing classifications of Crianza, Reserva, and Gran Reserva using economies of scale. There has been serious push back from important quality producers in the region, as the result of this bastardization is that a good Crianza is labeled the same exact way as a mass produced $7 one. This confuses consumers, who ultimately assume the same quality level given the identical ageing classification. Moving forward, Rioja’s goal should be to continue educating the market so it knows to avoid mass produced wine, as there are serious producers who are competitive at every price point. Ultimately, there is nothing inherent to ageing that makes wine better, and these ageing classifications communicate the opposite to consumers. Furthermore, the D.O.Ca. needs to reconsider its labeling and ageing designation practices, to avoid this bastardization in the marketplace.